LOOSE LEMUR

by Ben McGrath

AUGUST 4, 2008

Bill James, the Boston Red Sox senior adviser and resident skeptic, made his name by using statistics to debunk many of baseball’s truisms—by showing that much of what we think we see on a ball field turns out to be little more than an illusion when held up to the light of evidence. Then, after the Red Sox won their first World Series in eighty-six years, breaking Babe Ruth’s supposed “curse,” James published an essay, “Underestimating the Fog,” in which he seemed to backpedal on some crucial points. He suggested, for instance, that clutch hitting—long since dismissed by Jamesian rationalists as a myth—might exist after all, and that his colleagues just weren’t looking hard enough. Diehards in the statistician community wondered if James hadn’t gone soft with age, and begun seeing ghosts.

Several weeks ago, James was walking home from Fenway Park, after a Red Sox victory over the Kansas City Royals, when he came across a strange-looking animal with a speckled gray head. He at first took it to be a cat, but soon noticed a number of peculiar characteristics: the animal had large eyes on the sides of its head, a puglike face, and an extra-long tail (“like a broom handle”), and it moved with “an odd sashaying motion.” The moon was full. James was alone on the street. He stared at the animal for, as he later recalled, “a length of time which is probably six or seven times as long as the period that a fly ball is in the air.” The animal scurried under a parked car, at one point seeming to lift its hind legs over a stick in the road by using its tail as a kind of lever.

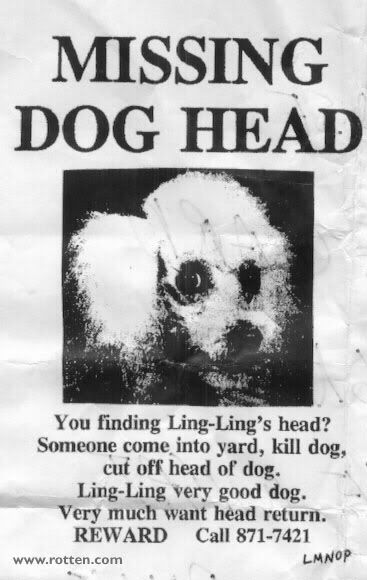

James quickly dispensed with the obvious candidates—dog, squirrel, raccoon, rat, skunk, possum—and began working his way down a checklist of more exotic possibilities: sloth, bear, porcupine, beaver. By the time he reached his house, he had decided that the animal he saw must have been a lemur. Lemurs are primates native to Madagascar, and by all available evidence, he realized, this was unlikely; the odds of stumbling upon a lemur living on the streets of a northeastern metropolis are a little like the odds of a baseball team’s going eighty-six years without a championship because of a curse. James says he called the local animal-control center, which informed him that his was the first Boston lemur sighting on record. (The Franklin Park Zoo, in Dorchester, has four ring-tailed lemurs, but all are accounted for.)

One of James’s friends discovered a report, on the Web site CryptoZoology.com, of a “strange lemur-like dog” spotted on a farm in Sherborn, Massachusetts, in 2002. (“It reminded me of a small, skinnier version of a Tasmanian wolf,” the poster, a filmmaker named Andrew Mudge, wrote.) Sherborn is twenty miles southwest of Boston, and James hypothesized that the lemur could have migrated in the years since and come to be living in the trees of a sanctuary in the area. The city, according to his theory, is an ideal habitat, because there are few natural predators, and the human demographics skew young and indifferent to wildlife. (James, by contrast, lived for most of his life in Kansas, where he saw enough skunks, possums, and raccoons to rule them out immediately.)

James eventually wrote a three-thousand-word account of his sighting and posted it on his Web site, which requires a subscription. “There is a lemur living wild on the streets of Boston, and if I have to be the first person to say so, well . . . that’s just the way it is,” he wrote. “I believe that if you set up a nocturnal observation camera at that location, you probably would wind up with footage of this animal, probably within a few days.” Several readers posted comments suggesting that the animal might have been a fisher or a stoat. “Not wishing to be dogmatic, in my mind it was simply a lemur,” James responded.

“I decided to report the sighting, against the urgings of my wife, who thought that I would get a reputation as a nut,” James explained in a recent e-mail. “I assume, if people start making fun of me for seeing a lemur, other people will step forward and say, ‘I saw something, too.’ ” No such luck yet.

Andrew Mudge, when reached by phone recently, assumed the call to be a prank. “Let me get this straight: you’re calling me about the lemur I saw in 2002?” he asked. “Which one of my friends put you up to this?” Mudge then recalled that he’d received an e-mail from a man named Bill James, but hadn’t paid it much attention. “I just remember having this gut feeling that this animal does not belong in this part of the world,” he wrote in an e-mail, thinking back to his sighting. “Ironically, I was leaving the house to go to a Red Sox game when this happened.” ♦

Owen is pawing my books. "Quit pawing my books Owen."

He didn't stop, yet.

It's 12:35 on a saturday

Fast forward a week.

Not much has changed. We still live the crumb life.

Yearly evaluations are coming up

.

I'm going to get six points deducted from my score because of the misplaced period on the last line.

Luckily, I accrued a decent savings point bonus in the spring.

Mother sends her love, but I only think she's doing good to have something to show during the evaluation.

I sneezed and I have a cough. I'll probably eat a cup of mushrooms tomorrow and I'll feel better. Horace better have some fresh ones down at the market and he better not have his fucking fish guts in the aisles again.

Back to today, it's 12:43. Not much has changed. Owen quit pawing my books. Now he's working on words for the evaluations.

"What word are you working on now Owen?"

He never answered. I imagine he said, "Pigeons" and then told a decent story of the gathering birds by the lamp post.

Caught here in a fiery blaze, I won't lose my will to stay.

I tried to drive all through the night,

the heat stroke ridden weather, the barren empty sights.

No oasis here to see, the sand is singing deathless words to me.

Chorus

Can't you help me as I'm startin' to burn (all alone).

Too many doses and I'm starting to get an attraction.

My confidence is leaving me on my own (all alone).

No one can save me and you know I don't want the attention.

As I to adjust to my new sights the rarely tired lights will take me to new heights.

My hand is on the trigger I'm ready to ignite.

Tomorrow might not make it but everything's all right.

Mental fiction follow me; show me what it's like to be set free.

Chorus

Can't you help me as I'm startin' to burn (all alone).

Too many doses and I'm starting to get an attraction.

My confidence is leaving me on my own (all alone).

No one can save me and you know I don´t want the attention.

So sorry you're not here I've been sane too long my vision's so unclear.

Now take a trip with me but don't be surprised when things aren't what they seem.

Caught here in a fiery blaze, won't lose my will to stay.

These eyes won't see the same, after I Flip today.

Sometimes I don't know why we'd rather live than die,

we look up towards the sky for answers to our lives.

We may get some solutions but most just pass us by,

don't want your absolution cause I can't make it right.

I'll make a beast out of myself, gets rid of all the pain of being a man.

Chorus

Can't you help me as I'm startin' to burn (all alone).

Too many doses and I'm starting to get an attraction.

My confidence is leaving me on my own (all alone).

No one can save me and you know I don't want the attention.

So sorry you're not here I've been sane too long my vision's so unclear.

Now take a trip with me but don't be surprised when things aren't what they seem.

I've known it from the start all these good ideas will tear your brain apart.

Scared but you can follow me I'm too weird to live but much too rare to die.

Rihanna's song is hot right now, and Trumbull isn't coming out until Sami finishes his thesis, so here's a review of track 1 of her LP:

Rihanna's song is hot right now, and Trumbull isn't coming out until Sami finishes his thesis, so here's a review of track 1 of her LP:1. SOS

Just hits so fucking hard. Turn it up. Bubbling beeps. Huge laser euro synth underneath driving it along. Pounding kicks and claps. Sounds like “TAINTED LOVE!” That’s it! 2007 version of tainted love with a hot black chick singing over it, yes please. This video has a part that’s like a corner of mirrors in a room of darkness. That even sounds kinda 80’s right? Rihanna is ill. Vocal layering used to the same success as on the entire Jeezy CD. This song is why I [bought] this cd. I’m glad I did.

Are Playoff XII's OK to wear to one of those? I think they should be.

Are Playoff XII's OK to wear to one of those? I think they should be. Nelly Furtado's new CD leaked. First listen was good. Alot of fans are like "she sold out sounds like everything else on radio etc." I can see why, and it's definitely a pretty far cry from classics like "Turn off the Lights" and "Try" but I'm sure its awesome in its own way. Nelly rules. She looked so hot on SNL.

Nelly Furtado's new CD leaked. First listen was good. Alot of fans are like "she sold out sounds like everything else on radio etc." I can see why, and it's definitely a pretty far cry from classics like "Turn off the Lights" and "Try" but I'm sure its awesome in its own way. Nelly rules. She looked so hot on SNL.

"I can't walk. I'm can't leave my bed," the 40-year-old Uribe, who weighs the same as five baby elephants, said in a recent telephone interview.

- Soundgarden tee

- Lord of the rings

- Hip headgear

- Dude wearing IV's

I'm sweatin' graduation, guys. 2 days ago I only had the C's. I need a 2.3 just to graduate. I'm in better shape now with the A, but I still got this Japanese film paper to turn in. I know I'm gonna do alright on it but still, I won't know until this professor turns in his grades if I actually graduate. Still keep getting "Class of 2006 Gift Program" mail.

comment challenge: change the lyrics of this song to fit your life and post it in my comments. i started to do it but then i remembered i have a paper to write. bye

As most of us are quite aware, human beings experience a phenomenon known as “the chills” when stepping into a modern van. In fact, for many of us, becoming a little “freaked out” when getting into vans, old and new alike, has been a life-long occurrence. But do you know why this happens?

As most of us are quite aware, human beings experience a phenomenon known as “the chills” when stepping into a modern van. In fact, for many of us, becoming a little “freaked out” when getting into vans, old and new alike, has been a life-long occurrence. But do you know why this happens?I propose that the reason behind this curious anomaly is that all vans are in fact ghosts, and that you should always exercise caution when deciding to enter one.

Have you ever noticed that when you are in a van, whether it be for travel, studying, or just hanging out, that you always end up either just fine or in the most horrible situation imaginable? It’s true. I polled 17 of my friends and they all said that they had traveled without any problems in vans on numerous occasions, yet each one had a handful of dreadful stories to tell involving breakdowns, the desert, parking tickets, break-ins, vagrants, tow trucks, break-outs, and random drug stops in

If it is taken as fact that all ghosts are either good spirits or menacing, haunted ghouls, this would explain the seemingly polarized results of my interviews. In other words, just as all normal ghosts are either good or bad, van ghosts are no different. There is information available on the internet regarding various tests one can perform to determine whether a van is a good or a bad ghost before entering it. The simplest one of all is to park it near an old

If you’ve ever bought an automobile, surely you’ve asked yourself, “Should I consider a van?” Before I answer that question, let’s review some more facts about vans. People who contemplate purchasing a van usually take into consideration that they tip over quite easily when making turns. This is what business people call a “necessary evil.” Auto makers insist that they really have no choice but to incorporate this flaw into the design of the vehicle when it is manufactured and merged with its soul at the assembly plant. Don’t be fooled by mathematicians who cite various equations and valencies to explain why an object such as a van would tip over…these men received their diplomas from modern Universities. Had they been schooled in the wisdom of the ancients, they might realize that all ghosts float. It seems rather silly then, to manufacture an automobile that is utterly incapable of touching the ground. Have you ever looked under all four tires of a van? You might have seen something alarming. A Thin layer of air. This quality is shared by ghosts and magnets, but not regular cars and trucks.

To return to the question “Should I consider buying a van?” the answer is "Yes," but be careful.

As a result of the digital revolution, you may have noticed an abundance of vans on the street these days featuring emblems of various internet service providers as well as a cadre of other businesses who are sustained by the demand for the World Wide Web. You might have entertained the notion late at night that the reason for this is that the internet is a ghost. This is not far from the truth. The internet is actually a network of ghosts who work together to create the energy to collect and allocate our constant stream of data. Who do you think counts the number of eggs you use every morning to make your omelet? The dog certainly doesn’t. No, this ever-flowing mass of data is collected by the dark forces of our world and stored on the internet. It follows then, that internet-related companies use vans and their ghostly powers to mend breaches in the world wide web.

Ghosts are all around us. They are part of our world. It’s not even our world, its OUR world. Vans are ghosts. When you enter a van, ask yourself, “Do I want to enter a ghost?” And if the answer is yes, you may want to think about how it would feel to be reincarnated as a ghost and then have people get in and out of you all the time. Just saying.